The story of Christmas features a miraculous astronomical sight. But this Christmas, we’re blessed with an abundance of new miraculous visions from the skies, courtesy of the James Webb Space Telescope, which lifted off on Christmas Day two years ago … from Jupiter and its rings (a mere 385 million miles away), to the Carina Nebula (7,500 light-years away), the Phantom Galaxy (32 million light-years away), and the deepest regions of space (13 billion light-years away).

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

In 1989, NASA began thinking about a successor to the Hubble Telescope. The new machine would have massive gold-plated lenses that could detect infrared light – invisible to our eyes, but capable of passing through dust and gases, 100 times farther into the universe. The Webb would also be much bigger than the Hubble: three stories tall and 70 feet wide, too big to fit into any existing rocket. NASA’s solution? Fold it up.

Scott Willoughby oversaw the Webb’s construction at Northrup Grumman. Ten days before launch in 2021, he explained to “Sunday Morning” the complexity of the unfolding process: “They have things that are called single-point failures – this has to move this way, and there’s only one of ’em. And Webb has over 300 of those.”

Three hundred things that had to go exactly right.

It took almost seven months for the telescope to unfold, calibrate, and reach its orbit, a million miles from Earth. So now, on the second anniversary of the launch, we asked how it went.

“It literally went perfect, as close to perfect as one could’ve even imagined,” Willoughby said. “People actually asked after, ‘Did you overblow how hard this was?’ And the truth was, practicing for everything as if it could go wrong was the best preparation for making it go right.”

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

Because infrared is a form of heat, it had to get cold—minus 400 degrees. Even the sun’s heat would blind the telescope to the faint infrared signals from space. And so, a large sun shield – an umbrella, basically – was deployed to block out any shred of the sun’s light from reaching the telescope’s lenses. “There’s only one star in the entire universe we’ll never see, and it’s ours, it’s the sun,” Willoughby said.

Finally, the science could begin.

At NASA’s Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Jane Rigby, the Webb’s chief scientist, talks to the telescope from the flight control room, drawing the data that has been collected. “The elevator pitch for the Webb Telescope was to get the baby pictures of the universe,” Rigby said. “We have delivered exactly what we promised on that topic. We’ve gone from basically ignorance about what that first billion years of the universe was like, to having it in crisp high definition.”

Another Webb mission: examining distant planets, to see if any of them have atmospheres like ours, maybe to find one human beings could live on. But how can a telescope know what’s in a distant planet’s atmosphere? Turns out, when a planet passes in front of its star, the elements of its atmosphere—oxygen, nitrogen, whatever—block specific bands of light. Analyzing how the spectrum of light changes can reveal what the atmosphere of that planet is like.

The Webb has already studied the atmospheres of dozens of distant planets. On one, the exoplanet K2-18 b, it found carbon dioxide and methane, which suggests that it has oceans. [It’s a mere 120 light-years from Earth.]

Rigby said, “It’s such a joy that this telescope is working so well, because it was built really well by the engineers.”

But not all the Webb headlines have been triumphant. One, in June 2022, didn’t sound good at all:

But Scott Willoughby was not worried: “We designed the mirrors to get hit by micrometeorites – you know, small particles, say grain of sand or something like that. But when you’re truly talking about one small spot in something 22 feet across? The impact of it was really irrelevant. It actually didn’t impact science at all.”

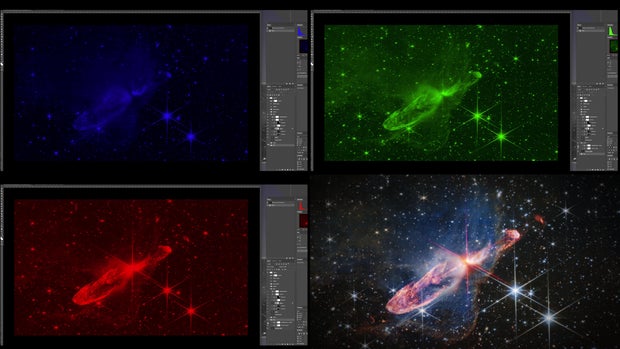

But there were also some questions about the photos. Was NASA manipulating them? Colorizing them? NASA image experts Joe DePasquale said, “That question actually comes up a lot: ‘Is what Webb sees real?'”

He and Alyssa Pagan can answer questions about colorizing, because they’re the ones who do it. “It’s our job to be able to translate that light into something that our eyes can see,” DePasquale said.

As it turns out, there’s a lot of light that people can’t see, like ultraviolet light, which bees can see; or infrared light, which pit vipers can see. Ultraviolet light travels in very short waves; infrared waves are much longer. And that’s what guides the colorizing process.

Pagan said, “We’re taking the shortest wavelengths, applying the bluer color; the middle wavelength, that’s the green; and then the longest wavelength gets assigned the red. This is what we think is the truest representation of what we could possibly see, if we could see an infrared light.”

NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Anton M. Koekemoer (STScI)

In just the first year of Webb observations, scientists published more than 600 papers based on its discoveries. And according to Willoughby, the telescope has one more little gift for us this Christmas: “When we launched, we never had to correct our own rocket engines,” he said. “We saved all of that fuel, and effectively on Day One, doubled the launch of the mission from ten years to 20.”

So, for at least 20 years, scientists around the world will keep peeling back the mysteries of the universe, and the Webb will keep sending back pictures that amaze and amuse us, from the optical quirk known as the question mark…to the galaxy cluster that NASA calls the “Christmas Tree,” and beyond.

For more info:

Story produced by Young Kim. Editor: Karen Brenner.